Like many people I might daydream over what I would do if I won the lottery, or if I suddenly came into an inheritance from a long lost rich uncle. Neither is likely given that I don’t play the lottery and I’m pretty sure that there are no golden apples hanging from the branches of my family tree, but still, I can dream. There are the obvious things: a nicer house, perhaps a villa in Cap d’Ail, the Ferrari (or two), expensive holidays, but what do you do when you’ve ticked off the predictable extravagancies? Well, I know what I’d do – I’d commission pieces of music. I’d become a patron of the arts.

For some reason, music lends itself to patronage particularly well. I’ve never heard of anyone commissioning an author out of altruism. Alas. Plays perhaps are different. Like music, theatre is a performing art and theatres will commission writers, but even then I’m not sure how often a play is paid for by someone with no direct interest. Paintings and sculptures may be commissioned, but that’s more of a retail purchase. The person paying gets the picture.

But my heroes/heroines are people like the Princesse de Polignac (aka Winnaretta Singer), who used her sewing machine wealth to commission music from the likes of Stravinsky, Satie and Poulenc, and Paul Sacher, the Swiss conductor and pharmaceutical billionaire whose fortune gave birth to pieces from Bartok and Stravinsky to Benjamin Britten and Elliot Carter.

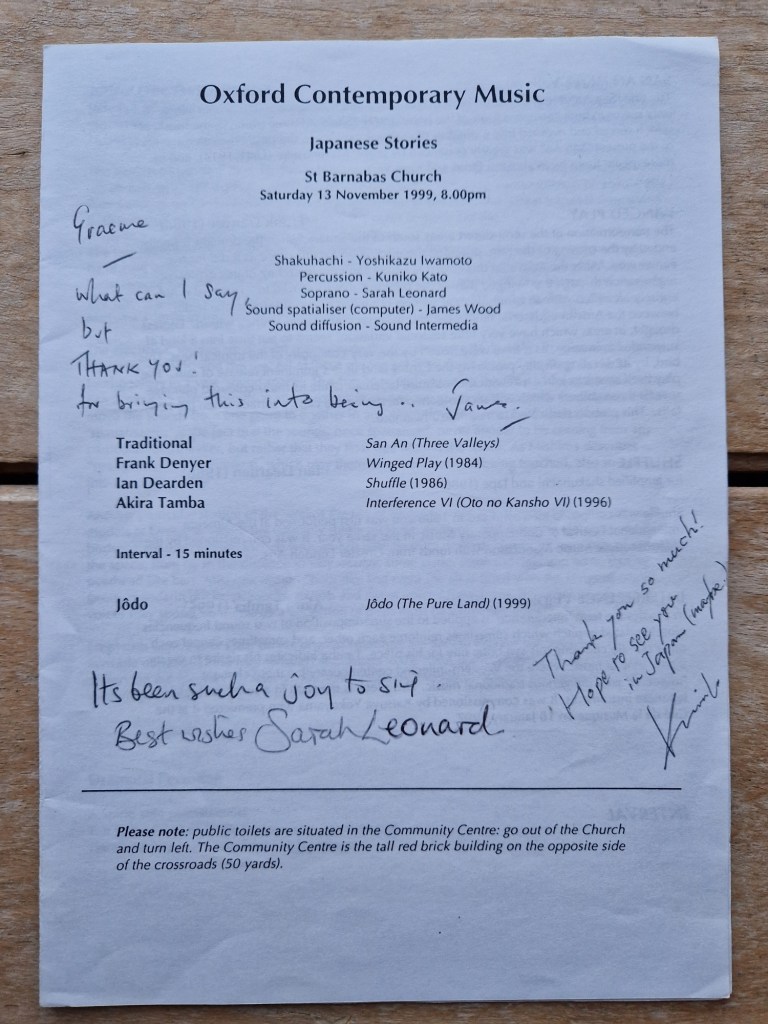

And once, just once (so far, anyway) I joined this illustrious company. This was back in the 1990s. I was working in Hong Kong with a good salary for the first time in my life, and through a friend of mine, Pippa Hyde, I commissioned a work from the percussionist and composer James Wood. The result was Jodo, a music theatre piece for soprano, percussion and electronics premiered in Oxford in 1999 with Kuniko Kato, the brilliant Japanese percussionist for whom it was written, and the soprano Sarah Leonard. I was always a great admirer of Sarah Leonard and was very sad to hear of her death last year.

Looking back from a distance of over 26 years, what do I remember about that 1999 premiere? Not a lot, to be honest. I remember being nervous in the company of James Wood, not wanting to make a fool of myself (and in turn embarrass Pippa), but what did I make of the music? I think I was a little underwhelmed. It seemed a strange piece. It is based on a short story by Yukio Mishima, The Priest of Shiga Temple and his Love, a peculiar story that tells of an aged priest who has renounced earthly pleasures in favour of Jodo – the “Pure Land” of a Buddhist heaven. I hope I may be forgiven for terminology that is no doubt completely incorrect in Buddhist theology, but I don’t know how else to express the concept. All is well until one day he catches a glimpse of the Great Imperial Concubine and her beauty shatters his convictions. Mishima tells of the emotional and spiritual anguish of both the priest and the imperial concubine, but the story itself ends ambiguously. In 1999 I struggled and had difficulty coming to grips with the theology behind the Pure Land. Today I feel a little different. I now appreciate the story’s open-ended nature and ambiguities, though it’s still a very elusive piece of writing that is hard to grasp. Just when I think I understand it, it slips from my hands.

After that 1999 concert, Jodo faded from my memory. I know it was performed in Japan in 2005, but now, finally, it has been recorded, with Kuniko Kato again and Anja Petersen, who sang the part that Sarah Leonard created, and released by Sargasso. Of course I bought it straightaway.

So what do I think of it now? I think it’s fabulous. There is some particularly beautiful electronics created at IRCAM. Describing the Pure Land, Mishima tells of instruments “which play by themselves without ever being touched” and of a “myriad other hundred-jewelled birds…raising their melodious voices in praise of the Buddha.” It’s not difficult to hear how this has inspired the composer. Kuniko Kato plays a variety of both Japanese and Western percussion as the priest, including brilliantly virtuosic drum and marimba sections. Anja Petersen’s high soprano alternates between cold haughtiness and doubt.

I don’t know whether I will ever get the chance to hear Jodo live again, but I now feel very proud that in my small way I helped this music come into existence.