Cemeteries are strange things, or rather it is our reaction to them that is often contradictory. The graveyard of an English country church nestled in the heart of the countryside can be a beautiful place, on the other hand I live in a converted church which we would never have bought if the graveyard was part of the garden. Thankfully it is over the road and out of sight. In Hong Kong apartments are cheaper if they overlook a cemetery, while traditional hillside graves are often in the most beautiful locations.

Some have become tourist attractions based on who is interred there. Highgate in London or Père Lachaise in Paris are, of course, the most well-known depending on whether your interest is in radical politics or 1960s music, but the one that speaks the most to me is the Old Protestant Cemetery in Macau. A quiet, peaceful gem in the middle of the city and which started a writing project that for me has become enormously fulfilling.

Old Protestant Cemetery, Macau

The cemetery was founded in 1821 to provide a protestant burial ground in Catholic Macau. Next to the cemetery is Casa Garden, a salmon-pink and white building that was the East India Company’s base when Macau was the centre of its China business.

Casa Garden

A later addition was the plain, simple white-walled Morrison Chapel.

Morrison Chapel

The result is a haven of peace where the graves and memorials stand in the shade of frangipani trees. Most of those who were buried there were British, American and Dutch sailors and missionaries, but also their families and some of the most tragic are the infants such as Charlotte M Livingstone who died in 1858 aged 5 months and 10 days, and the even younger Charles Hodge who died in 1857 aged 2 months and 6 days. Of course there was nothing unusual in infant death in those days, but there’s something particularly heart-breaking when it occurs so far from home.

At the other end of the scale from small stones to the memory of children are the large, grand memorials such as that to Lord Henry John Spencer Churchill.

The cemetery closed in 1858, by which time most British and Americans had moved to Hong Kong, and gradually fell into disrepair. It wasn’t until the 1950s and 60s that the cemetery was restored and documented primarily through the efforts of the University of Hong Kong Vice-Chancellor Sir Lindsay Ride and his wife Mary. Their book “An East India Company Cemetery” is a testament to their love of the place and to the work they put into bringing the cemetery back to life (as it were). It’s well worth reading if you can get hold of a copy. Lindsay Ride’s own ashes were interred there in 1977.

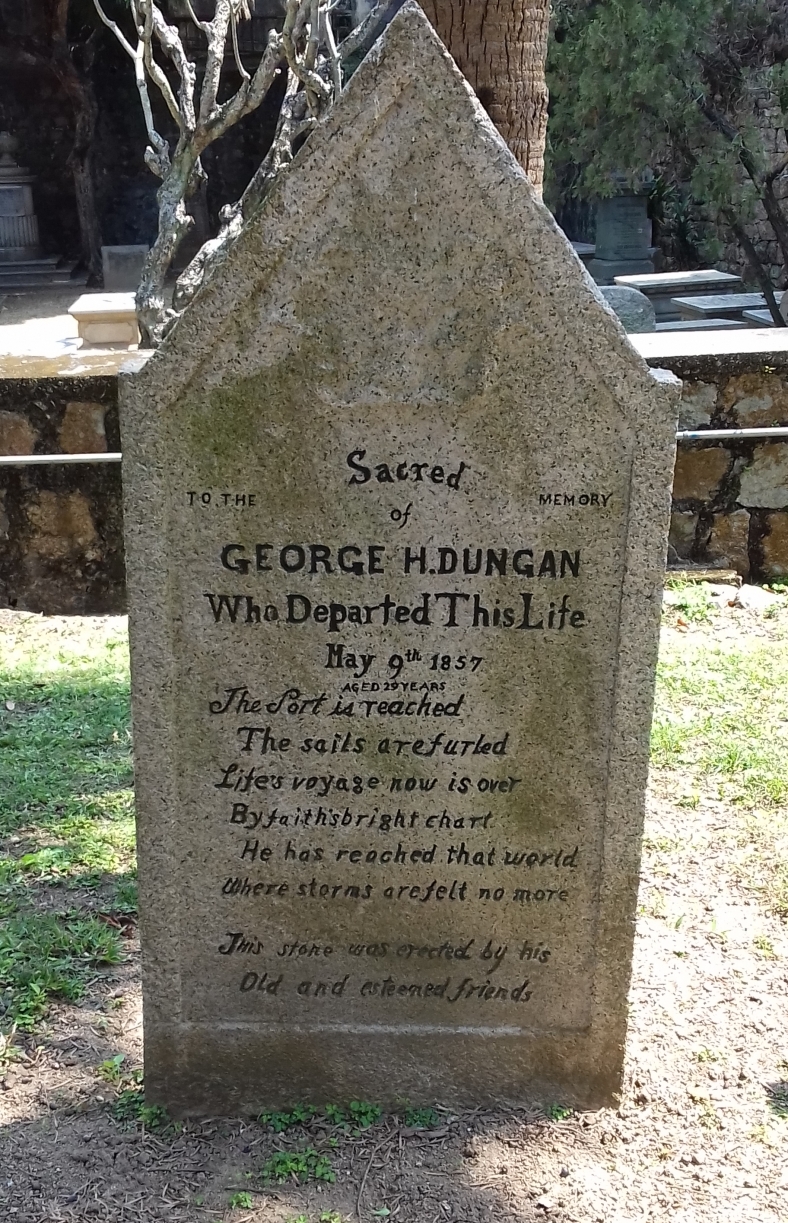

At a personal level it was thoughts of the cemetery that set me on the course of writing about Macau and realising just how many stories there were to be told about this remarkable city. I am really excited that the fruits of this obsession will be available for all to see in August when Fly on the Wall Press (https://www.flyonthewallpoetry.co.uk/) publish my first short story collection “The Goddess of Macau”. Until then, you can still read my first Macau story (“Sacred to the Memory”), which was directly inspired by the cemetery and this grave stone in particular, https://www.litro.co.uk/2015/04/sacred-to-the-memory/.